Todd Jay Leonard, Blog

The area where I live in Japan, which is actually geographically located further north than Indiana, enjoys a stunning fall season. The trees gradually turn hues of red, orange and yellow before the leaves float to the ground, signaling the rapid approach of the winter season.

Autumn in Japan, just like in Indiana, signals not only the end of summer, but harvest time. The telltale sign that fall has arrived in Japan is the hustle-bustle of the farmers who work feverishly from sunup to sundown to bring in their crops.

Of course, instead of fields of corn as far as the eye can see, rice paddies dot Japan’s landscape from north to south.

Whenever I call my dear friend Chris Wissing, in rural Manila, her husband, Mike — true to his farming roots — always wants to know: What’s the weather like over there?

American farmers are obsessed with the weather, and Japanese farmers are no different. They too have to try to guess when is the best time to bring in the crops in order not to risk lowering their yield; or worse, losing product due to an early frost.

Growing rice is especially tricky because the conditions must be just right for it to grow to maturation.

When I first relocated to Japan, there was an unseasonably cool summer one year, which caused severe damage to the rice plants. For germination to occur, rice grows best in climates that are humid with high temperatures.

However, that particular year was an agricultural nightmare because of the cool summer weather that plagued the entire archipelago. Very little rice was harvested, leaving Japan in a very precarious situation. How would Japan be able to supply its people with the favored Japonica variety of short, sticky rice?

The only option, and one that Japan tried to avoid but ultimately could not, was to import rice from other countries, such as Australia, Thailand and the United States. It was a sobering moment for the farmers and Japanese people in general.

Japanese people tend to prefer homegrown rice to imported rice because it is believed the quality of Japanese rice is superior to other countries’ products. Also, the texture is glutinous, which makes it “sticky,” a feature that Japanese people insist upon.

It would be akin to Hoosiers being forced to import “sweet-corn” from South America; even though it may be just as good as Indiana’s, there is a certain degree of snobbery involved, and the average Hoosier would much rather have fresh, Indiana-grown corn as opposed to an imported facsimile.

Since rice (kome in Japanese) is the principal crop of Japan and is believed to have been introduced initially by either China or Korea during the Yayoi Period (circa 300 B.C. to 300 A.D.), the history of rice production extends to the very core of the Japanese-self.

The entire Japanese extended family system is believed to have evolved around the rice culture: planting, cultivating, and harvesting.

Traditionally, rice farming required an inordinate amount of communal cooperation between families and neighbors due to the great care it takes to grow the rice, which includes a very sophisticated system of water irrigation that oftentimes must pass through a neighbor’s paddy to reach one’s own paddy.

Through this type of communal cooperation, the agricultural system developed thousands of years ago which has helped to mold Japanese society and culture to what it is today.

This, in part, is why Japanese people work very hard to maintain harmony (wa) between neighbors and colleagues in order to avoid strife and conflict.

As a people, or society, Japanese have learned how best to live within a tight-knit community through this type of cooperation.

With such a long agricultural history, as expected, the planting and cultivation of rice gradually took on religious implications over the millennia, and many festivals occur each spring and autumn to honor Shinto deities connected to this all important staple food.

Many years ago, an American friend who married a Japanese farmer invited me to experience harvesting rice. It was quite an operation from start to finish, which makes me much more mindful of the process and work involved each time I pick up chopsticks to shovel rice into my mouth.

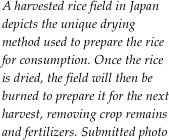

My particular job was to go along and gather the bundles of cut rice; these then had to be balanced on poles (using only a small stick tied with twine at the base) so it could dry.

There was certainly a skill to doing it properly, because on more than one occasion the entire stack tumbled to the ground forcing me to start the process all over again.

My friend’s father-in-law was quite entertained throughout the day by my antics. Even though I hail from Indiana, my time spent in a farming environment is severely limited.

After the rice dries and is removed from the fields, the stubble that is left on the ground is then burned. Every year, when the wind blows in a certain direction, the streets of my city are blanketed in a smoky haze that permeates every nook and cranny.

I asked a farmer-friend here why Japanese farmers burn the fields every year, and he explained to me that coupled with fertilization, this is the best way to maintain the ground so that it can be cultivated year after year without any ill effects to the soil. Somehow the scorching effect has a positive influence on the soil.

Besides rice, the area where I live is well-known for its delectable apples. Again, the process of harvesting apples is amazingly intricate, involving individually wrapping by hand each apple while it is still on the tree.

Immediately before the apples are picked, the wrappings are removed and metallic-reflective sheets are laid on the ground around the trees to insure that each apple has just the right coloration.

More details on this, as well as an interesting Indiana connection to the Japanese apple industry, will be offered in my next column.

By TODD JAY LEONARD

Columnist

Japanese harvest is similar to Indiana’s

Monday, October 10, 2005