Todd Jay Leonard, Blog

Attending a traditional Japanese Shinto wedding is quite a unique and memorable experience. I have attended a number of church weddings and Japanese-style receptions over the years while living here, but only once have I had the privilege of attending a traditional Shinto wedding ceremony.

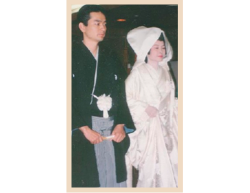

Most Japanese consider themselves to be both Shintoists and Buddhists, usually opting for a Shinto wedding and a Buddhist funeral. Few cultures offer the opportunity to glide so easily between religions; but Japanese culture does, and aspects of both religious traditions are everywhere you look in Japan.

Many people maintain both a Buddhist altar and a Shinto shrine in their homes. Many businesses will display a small Shinto shrine, as well as invite a Shinto priest to bless the construction of a new building.

Families invite Buddhist priests to chant sutras during the O-Bon season (the August holiday when ancestral spirits are invited back to the home) and to perform ceremonies during the anniversaries of loved ones’ deaths — combining and borrowing from both religious traditions.

A traditional Shinto wedding ceremony is beautiful in its solemnity and ritual. The bridal couple wears traditional costumes. The groom wears a hakama (a pleated pant-like garment) with a black kimono jacket. The family crest of the groom is usually emblazoned on each side of the upper front of the chest portion of the kimono.

The bride wears a pure-white, delicately embroidered silk kimono (called a “shiromuku”) with long sleeves that reach past her knees. The long sleeves signify she is single; once married, she will wear only short-sleeved kimonos, indicating that she is married.

The white color of the kimono dates back to the days of the samurai, when a woman would show her submission to the family she was marrying into, conveying “I submit myself to you to be dyed any color to conform to your family’s wishes and social standing.”

In addition to her white kimono that drags around her feet as she walks, she wears elaborate white makeup and a traditional wig that most Westerners associate with that of what a geisha might wear. Over her wig, she wears a white silk covering. This headpiece is traditionally used to hide the bride’s “horns of jealousy.”

The ceremony is performed by a Shinto priest and is attended by two shrine maidens who assist in the ritualistic portion of the ceremony. Because Shintoism is an animistic religion revering nature, dating to time immemorial, the ceremony reflects much symbolism connected to its nature-worship tradition.

The elaborate ritual surrounding the exchanging of nuptial cups of sake, though, is the most important part of a Shinto wedding. Blessings are bestowed upon rice wine (sake), where three cups are stacked neatly on a wooden stand near the Shinto priest and wedding couple. The bridegroom first takes the topmost cup, and the shrine maiden delicately pours sake into the cup.

Carefully, the groom takes three small sips signifying “san-san-kudo” or the deepening of the relationship to form a stronger connection between the wedding couple. The groom then hands the cup to his bride, and it is re-filled and she repeats the ritual.

This is then reversed for the second cup, with the bride first partaking of the sake in three sips before handing it to the groom. Just as in the first cup’s ritual, the couple then each partakes of the sake from the third cup.

Each guest in attendance also drinks a bit of the rice wine, further solidifying the new union which extends to the families.

Traditionally, Shinto weddings were held in actual shrines, but today most are held in hotels that have recreated exact replicas of shrines on the premises.

I remember being awestruck when I arrived at the appointed room that looked to me like an ordinary banquet room from the outside; when the doors opened, however, a beautifully constructed wooden shrine, perfectly designed for wedding ceremonies, was revealed.

Unlike in the United States, this ceremony doesn’t necessarily mean the couple is legally married. A secular registration at the city office (where the proper papers are submitted by the bride and groom) actually legalizes the union.

The wedding itself, and the lavish reception that follows the ceremony, has no bearing whatsoever on the couple’s legal status as husband and wife. It only becomes legal once the marriage notice (konin todoke) is submitted and registered, which is similar to the European tradition and custom of legalizing marriages.

A friend of mine once had a huge wedding party to satisfy her parents’ desire that she marry before they died. It had all the makings of an authentic wedding, except she never registered it formally … and hence was not really married in the legal sense, just the social sense.

Her parents were satisfied that the “appearance” of a marriage took place. They never knew that she and the man they thought she married never registered it with the city office. It also kept prying neighbors and relatives from gossiping about why she hadn’t married, even though she was past the normal marrying age.

Interestingly, a cottage industry has recently been created for foreigners to perform weddings in hotel and wedding-hall chapels all over Japan. Just like the recreated shrines, hotels also offer the wedding couple the option of a “church” wedding — with an authentic-looking country chapel and a foreign minister to perform the ceremony.

The problem is that most of the ministers who perform the weddings are English teachers with no ordination papers. Because the weddings are not legally binding and are mostly for show, there is nothing illegal about a person impersonating clergy or ministers in Japan.

Besides, the majority of the couples who have “Christian” church weddings are not even Christian, but are Buddhist … or Shinto … well, probably both.

By TODD JAY LEONARD

Columnist

Traditional Japanese weddings are beautiful

Monday, September 12, 2005