Todd Jay Leonard, Blog

Green tea is the Japanese beverage of choice in the mornings, when entertaining guests in the afternoon and when taking a break. It is the only type of traditional tea grown in Japan, and it is served plain without any milk or sugar. For the first time drinker, it may seem bitter; but just like coffee, it grows on you.

When my cousins came to visit, they were so excited to try green tea that on the airplane ride over they asked for it. When the flight attendant served them, they asked her for milk and sugar. I guess she shot them a look of complete horror, announcing incredulously: "It's green tea, not English tea."

They responded that they knew what it was, but still wanted the milk and sugar. Begrudgingly, she gave them what they wanted. I am sure she was surprised, or maybe even shocked, that they would defile green tea with something as crass and vulgar as sugar and milk.

Green tea is much more than a beverage; it is a national pastime, a cultural institution of sorts, that incorporates the aesthetic beauty of nature, the creativeness of art, the ritual of religion, and culminates in a solemn rite of social interaction between the tea master and his/her guests in the "tea ceremony" ("sado," meaning "the way of tea" in Japanese).

Green tea originally came to Japan via China during the Nara Period (710-794) by Buddhist monks who brought tea seeds back to Japan with them. However, it wasn't until 1191 that an industry surrounding the cultivation of tea in Japan truly began. It is believed that a monk named "Eisai" planted seeds he brought from China and hence encouraged the widespread cultivation of tea.

Today half of all the tea grown in Japan comes from Shizuoka Prefecture south of Tokyo. When I was a high school exchange student in Tokyo, my host family took me on the bullet train for a short vacation to Atami in eastern Shizuoka.

On our trip, we went through "tea country." The perfectly manicured terraced tea fields were a wondrous sight to see from the window of the speeding train. Rows upon rows of tea plants covered the rolling hills of the mountains throughout the countryside. Women were bent over in broad-rimmed straw hats busily picking the tea leaves.

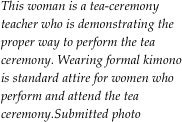

For visitors to Japan, attending a formal "tea ceremony" is indeed a treat. When my mother first visited Japan, we were invited to partake in a tea ceremony. All of the women in attendance wore beautiful silk kimono.

The tea ceremony is very formal and highly ritualized. Much care is taken by the host to select just the right combination of bowls and utensils to use, the perfect dry sweet that is eaten with the tea, and what decorations to use in the "tokonoma," or alcove, located in the tea room.

Guests approach experiencing the tea ceremony with a sense of reverence and respect for the ritual itself, but also toward the host who has made painstaking preparations, taking into account the season to match aesthetically colors, textures and flavors to make the ceremony a once-in-a-lifetime event.

In fact, each time the tea ceremony is performed, it is regarded as a singular occurrence or event that cannot be repeated exactly - the same season, the same guests, the same sweets, the same atmosphere. That moment in time can only happen once, and can never be exactly replicated.

The tea ceremony requires that guests sit "seiza" (sitting on one's knees). For Japanese, this is not a problem, as they are able to sit for endless periods in this position. Not so for people who aren't used to sitting like this for long periods of time. My mother, after about 20 minutes, finally leaned over and told me she couldn't feel her legs.

An astute guest sensed my mother's discomfort and retrieved for her a small stool that allowed her to sit in the proper position, but shifted the weight from her legs to the stool. This made my mother very happy, and allowed her to enjoy the tea ceremony more fully.

Actually, foreign visitors are given much leeway in the etiquette department when it comes to the tea ceremony. It is such a foreign concept to anything that we experience, that most Japanese hosts forgive most indiscretions regarding the proper procedure and ritual associated with the tea ceremony and accommodate first-time visitors accordingly.

Upon arrival, guests for the tea ceremony are ushered into a waiting area where they are able to sample the hot water used in the ceremony. Oftentimes, the guests will select from among them the "main guest" who will act as leader of the group. This is usually an esteemed person who is a teacher or elder of the others.

Once the host acknowledges them, they are led by the main guest to the tea garden where they may sit for a few moments on benches to enjoy the natural beauty of the meticulously kept garden.

If available, the guests will ceremoniously wash their hands in a "tsukubai," or stone basin. This is largely symbolic, representing that the guests cleanse themselves of any worldly concerns before entering the actual tea house. The order that the guests rinse their hands is the order that they will be served throughout the entire tea ceremony.

A true tea house requires that the guests crawl through a small sliding door called a "nijiriguchi." This requires that the guests crouch low on their knees to enter the room. I was told this symbolizes the idea that all are considered equal and no one person has status or prestige over another while in the confines of the tea room.

Each guest upon entering the tea room reverently admires the scroll hanging in the alcove (selected for the occasion and the season). They then seat themselves around the edge of the room in the order they decided earlier during the cleansing in the garden.

The host then prepares the tea in a very systematic and practiced manner that represents centuries of tradition. The tea is powdered and mixed with hot water from an iron teapot using a wooden ladle. The host then whips the tea with a traditional whisk made from bamboo. The main guest is served the first bowl of tea by bowing to the host before picking the bowl up and cupping it in both hands. The bowl is turned three times before taking the first sip.

Many tea masters have studied and honed their ability for decades. My university has a tea ceremony club, and many of the students who belong have studied it since they were in elementary or junior high school.

It is certainly a very representative part of Japanese culture, and any visitor to Japan, if given the opportunity, should experience this traditional art form.

Just don't ask for milk and sugar for your tea.

By TODD JAY LEONARD

Columnist

Japan's beverage

Tea isn’t just a drink; it’s a ceremony

Monday, October 23 , 2006