Todd Jay Leonard, Blog

Coming in as No. 8 on my "Top Ten List" of things I like about Japan is the custom of "gift giving."

I'm sure all cultures perform a similar time-honored gift-giving ritual, but there is something institutional about the way Japanese give and accept gifts, making it an ingrained and essential component of their rich and vibrant culture.

Officially, there are two times a year that Japanese give gifts - chugen, in midsummer, and seibo, at the end of the year. Stores put up elaborate displays during these two seasons in an effort to lure customers into buying the exquisitely wrapped packages.

Often, however, these gifts are not given without some strings attached, meaning there is sometimes a strategic reason for giving a gift of a certain value to a particular person. Perhaps the giver had been assisted prior to the gift-giving season and hence feels an obligation to repay that assistance with a gift; or perhaps the gift-giver is anticipating the need to ask a future favor of the receiver, and an expensive summer or year-end gift will help ease the burden of asking for that assistance.

In either case, the gift can be a sort of bargaining chip with the other person.

This is not to say these types of gifts aren't ever given just for the sake of giving, because in most instances, they are offered without any future expectation or ulterior motive. Japanese people, in general, are a wonderfully generous group of people, making gift-giving a natural part of their cultural being.

Gifts here are sometimes used to cancel out obligations to others as well. For instance, if you do me a favor and I reward you immediately with a "thank you" gift, then I have effectively neutralized the obligation I might have to you.

Thanks, neighbor!

Once, when I had a group of students to my home for a barbecue, we wanted to take a group picture. Since everyone wanted to be in the photo, we needed someone to take it. Since my neighbor was working in the yard, he was the logical solution to our dilemma. Happily, he came over to take our picture, and I, of course, thanked him for doing this.

As he was exiting the backyard, one of my female students very naturally, and without consciously thinking about it, reached down to the table and picked up an unopened package of cookies that she then elegantly, and quite effortlessly, offered to him as he departed.

I thought at the time, "Boy, she's smooth." The whole transaction occurred in one well-ordered glide of her hand, thus canceling out any obligation we might have had to him for doing us this favor. It was a natural, cultural reaction for her to do this.

In the United States, a simple "thank you" would have sufficed, and no one would have felt the need to give anything further to the person for doing something as mundane as snapping a photo.

On another occasion, I was surprised by a neighbor who lived one street over. He and his daughter showed up at my door bearing a gift basket of beautiful homegrown apples in pristine condition. I was not so familiar with this neighbor and, in fact, he had to explain to me where exactly his house was located. Also, he admitted to me that we had never actually met in person, but we had greeted one another on the street from time to time.

Sudden generosity

One disadvantage of being a foreigner in rural Japan is that we stand out so much that everyone knows who we are, but often we have no idea who everyone else is.

In this case, however, I was at least marginally familiar with him, but his sudden generosity made me a bit uncomfortable and somewhat suspicious of his motives. Why, I kept wondering, did he go to all the trouble to visit me - out of the blue - and why did he make a point of bringing his daughter along?

It took only two days to learn the answers to these questions and, in turn, his motives for the rather unexpected (and certainly abrupt) act of previous generosity: He was hoping that I would agree to tutor his daughter in English.

She was preparing to take the entrance exam into high school and needed supplementary lessons to get her up to snuff. Mystery solved.

Fortunately for me, and unfortunately for her, I was going abroad during the time she needed the lessons, thus relieving me of any obligation. Be that as it may, I still felt a hint of indebtedness to this neighbor for the gift of apples I had received before.

With a little quick thinking on my part, I remembered I had a bag of "kaki" (Japanese persimmons) which had been given to me a day or so before by a student. Excusing myself momentarily, I gathered an assortment of these fruits and offered them to my neighbor, thus effectively canceling out any obligation I had - in kind - to him and his daughter.

Re-gifting

The "recycling" of gifts is commonly practiced in Japan - as long as they are in their original, unopened packages or in the case of fruits and vegetables, fresh and in impeccable condition. Not being a huge fan of persimmons, however, I was happy to not only cancel out my prior obligation but to also unload something that likely would have gone to waste. A win-win situation.

When invited to someone's home in Japan, it is customary to arrive with some sort of gift-offering. It can be a small bunch of cut flowers, an assortment of fruits or cakes for dessert or a bottle of wine - just about anything. Again, this offering helps to cancel out any obligation that might have been incurred by "imposing" upon the host.

This particular gift-giving custom is now so firmly a part of my cultural-being that whenever I am invited to someone's home for a meal or coffee, whether in Japan or the U.S., I feel it necessary to contribute some sort of offering as a "thank you" gift to the host.

It is such a nice custom. Americans certainly don't expect gifts from guests, but appreciate the gesture all the same.

After so many years of cultural conditioning in Japan, I feel naked arriving to someone's home for dinner without some type of appreciation gift in hand.

I have acculturated so much to this custom that I even feel the need to bring some sort of souvenir or gift from Japan to family and friends back home. I feel odd arriving back to Indiana without something to give the people I meet. The problem is, I've exhausted all of the possible options, having given just about every type of Japanese trinket and bauble imaginable.

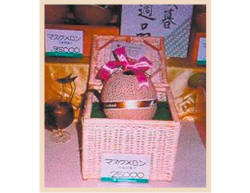

The Japanese have perfected the art of gift-giving into a national virtue. From small mom-and-pop shops to huge department stores, nearly all of these enterprises offer "gift-wrapping" as a matter of course (and free of charge) to all their customers.

One can't swing a samurai sword here and not hit a place that has ready-made gifts for the picking. Every train station, airport, and tourist attraction - as well as a myriad of other public places - have counters where "omiyage" (souvenir gifts) can be purchased.

Business people who must travel away from their office on an official trip nearly always return with some sort of omiyage in the form of food for the entire office to enjoy. It is expected by the person's colleagues and is a firmly rooted custom in Japanese business culture. These gifts come in a variety of sizes (depending on how many people are in the office), and each cake or cookie is individually wrapped for easy distribution.

One valuable lesson I have learned while residing in Japan is never to look a gift-horse in the mouth. I graciously accept whatever is offered - even if it is something I don't need or even want. After all, I can always recycle it.

By TODD JAY LEONARD

Columnist

It is good to bear gifts

In Japan, it's the gift that counts

Monday, July 16 , 2007