Todd Jay Leonard, Blog

Few occurrences in life are sadder and more disturbing than when a young person's life is cut short. It is indeed tragic if this occurs through illness, an accident or by the hand of another. It is especially heart-rending when it is through suicide. Those who are left behind forever wonder if something could have been done to prevent what occurred.

In recent months, Japan has been rocked by a rash of student suicides. At the crux of this quandary is the sad fact that each of these cases is the result of bullying.

In one particularly disturbing case, the student's teacher had encouraged the bullying by participating in it himself. As expected, the other students in the class intensified their bullying with the seeming approval of the teacher, interpreting his poor judgment as a sign of being able to do what and as they wished.

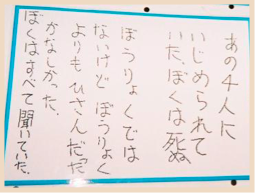

The bullied student hanged himself at the school. Ironically, in a bizarre twist, the student specified in his suicide note that any money left over after his funeral be given to his homeroom class - the very people who made his life so miserable that he felt he had no choice other than to kill himself. Even in death, he seemingly tried to seek their approval.

Collectively, as a society, there has been much hand-wringing in Japan over the past couple of months, trying to come to some sort of conclusion as to why this is happening and with such frequency.

Bullying or "ijime" has always been a problem in Japan, but one difference today is the constancy in which it is occurring, causing politicians and educators alike to speculate if it is indeed bordering on becoming a full-fledged epidemic.

It seems like a week hardly went by in recent months that the nightly news report didn't begin with yet another suicide case by an elementary or junior high school-aged child; video footage of the telltale vase of flowers sitting on the lone desk in an empty classroom, marking the deceased student's seat.

Of course, fingers are being pointed in every direction. Parents point to a breakdown in the school system where supervision of students is perhaps lax and a bullying mentality is either overlooked or even ignored; administrators point to the teachers, saying they should have been aware of the bullying which occurred under their noses; teachers pointing back at the parents and schools saying they can't possibly stay on top of the situation with such a heavy workload, which includes the huge responsibility given to them as "homeroom" teachers who must oversee the "moral" education of the children in their care. The blame game coming full circle.

Rarely in Japan is one segment of society held accountable, taking responsibility categorically. Instead, blame is compartmentalized or divided somewhat equally over several components, making it difficult to discern or pinpoint exactly who is at fault or what exactly happened.

As one well-known expert on Japan noted in his book "The Enigma of Japanese Power," Karl von Wolfren wryly concluded that the "buck" never really ever stops in Japan, but continues to get passed around until it doesn't really matter anymore.

For the sake of the children in extreme peril, I hope this will certainly not be the case in this instance. Alarmed by the sudden surge in preteen and teen suicide, the Prime Minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, instructed a newly appointed council on education reform to make this a priority, calling for sweeping and strict measures to be implemented against students who bully and teachers who participate in bullying (or who fail to take appropriate action when a bullying situation is known).

To outsiders, these criteria seem like no-brainers, but this shift in policy is quite unprecedented. A prevailing attitude in the past has been - perhaps unintentionally - to blame the victim by insisting the bullied students toughen up or try to adapt and fit into the standards set by the majority of the group.

Prime Minister Abe already broke with standard political protocol by sending a personal advisor on his behalf to southern Japan to meet with officials at the scene of one of the suicides. This act was unparalleled, considering that his predecessors in the past never bothered to intervene so directly.

The idea that day after day, a bullied student is forced to engage with those who are the tormentors is unfathomable. Is it any wonder, then, that the bullied children feel they have no other choice?

In Japan, instead of teachers maintaining a classroom where students must move around the school to attend various classes with different classmates in each class, Japanese students are assigned to a "homeroom" class where the teachers come to the classroom to teach the lessons. All teachers have a desk in one big "teacher's room." So, for the most part, Japanese students are in the same classroom with the same classmates the entire time they are in school.

For a bullied student, this is a living nightmare. Between classes, students are largely unsupervised, as the teachers all return to the teacher's room to prepare for the next lesson. Students congregate in the area around their classroom, which means that bullied students are at the mercy of the bullies who have free reign during these breaks, at lunch and before and after school.

Perhaps changes will be made, now that the Prime Minister seems so keen on reforming education in Japan, cleaning house, so to speak, rather than merely paying lip service to pacify voters. Only time will tell, and in the process, I hope that Japanese teachers have finally realized that ignoring bullying will not make it go away. Nipping it in the bud will.

By TODD JAY LEONARD

Columnist

Student suicide

Japan’s prime minister takes steps to curb bullying

Monday, January 1 , 2007